Meta’s Data for Good team recently released a fascinating dataset on cross-gender social ties around the world. The data comes from a research paper that measures how gender-segregated or gender-mixed social networks are, based on Facebook friendship patterns across 178 countries and tens of thousands of sub-national regions.

The key metric is the Cross-Gender Friendship Ratio (CGFR): the ratio of cross-gender friendships to same-gender friendships within a given radius. A CGFR of 1.0 means people have as many cross-gender friends as same-gender friends. Lower values indicate more gender-segregated social networks.

Being Turkish and having lived in both Turkey and the US, I was curious to see where Turkey stands. The results were striking, but not entirely surprising.

Turkey’s Position

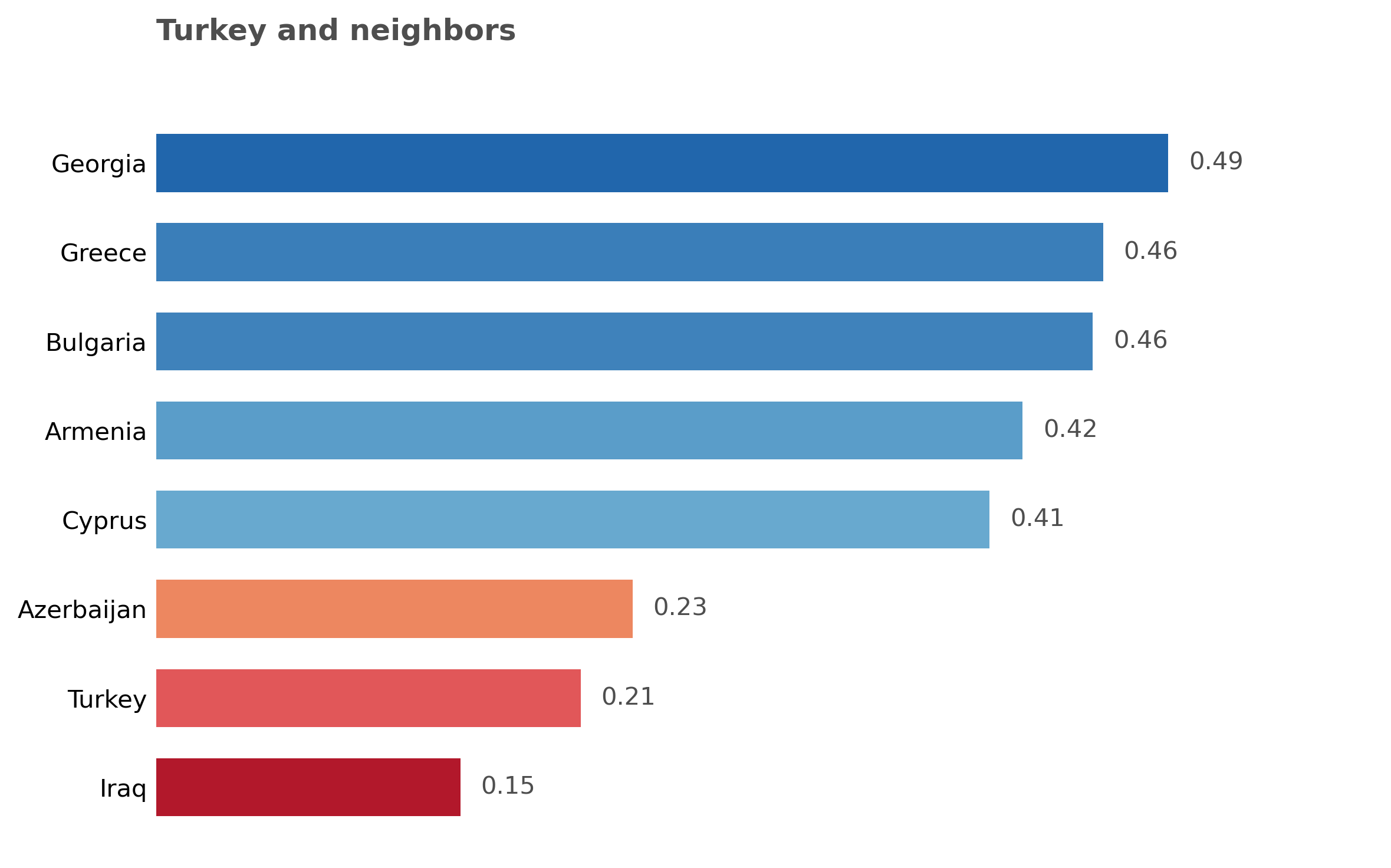

Turkey has a CGFR of 0.207 at the 50km radius, ranking 168th out of 178 countries globally. This places Turkey in the bottom 6th percentile worldwide. Among its neighbors, only Syria and Iraq have lower scores. Greece, just across the Aegean, has nearly double the ratio (0.40).

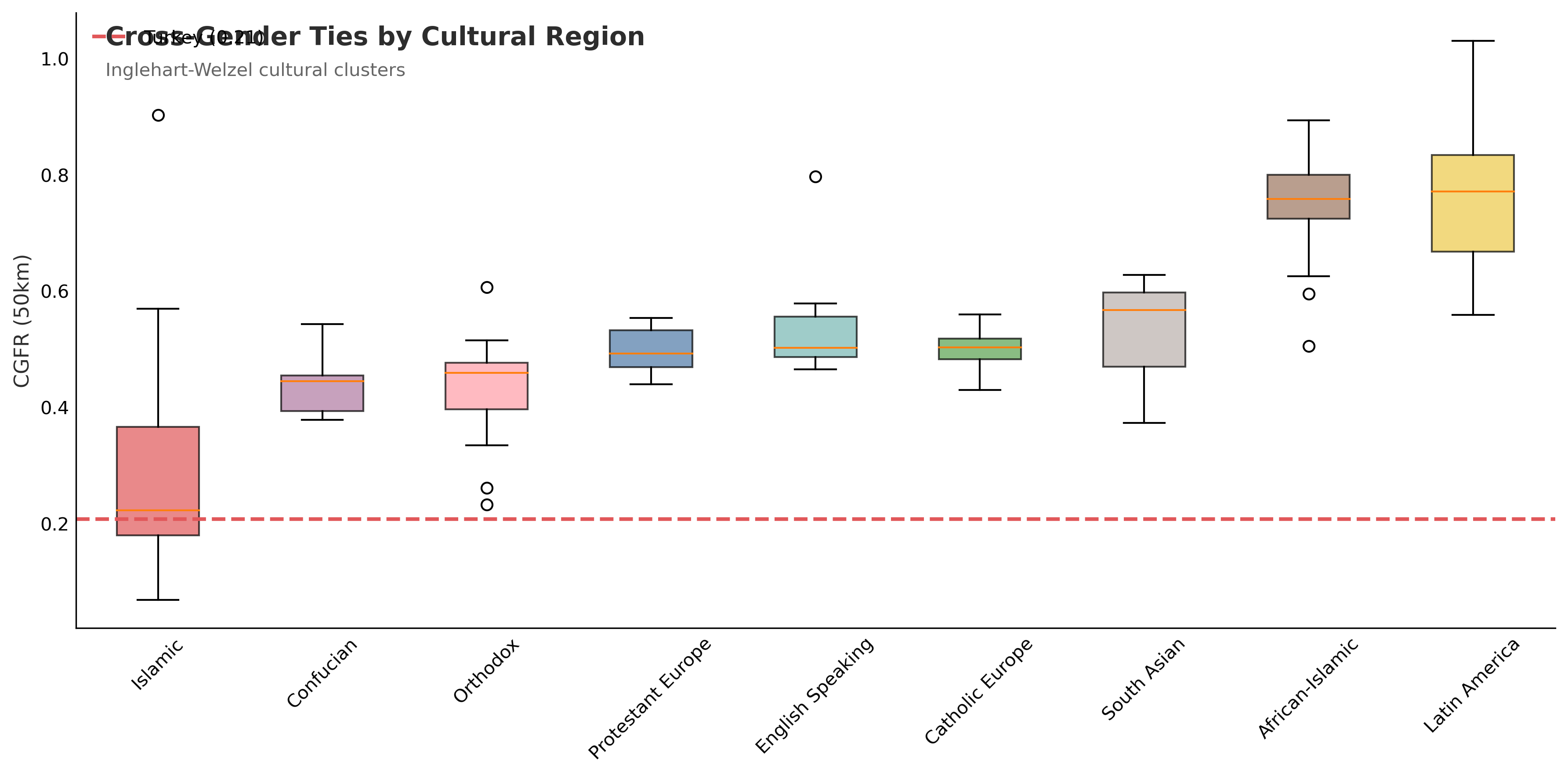

For context, here’s how different regions compare:

| Region | Mean CGFR | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Global (178 countries) | 0.56 | 0.07 - 1.06 |

| Europe (39 countries) | 0.47 | 0.21 - 0.60 |

| Turkey | 0.21 | — |

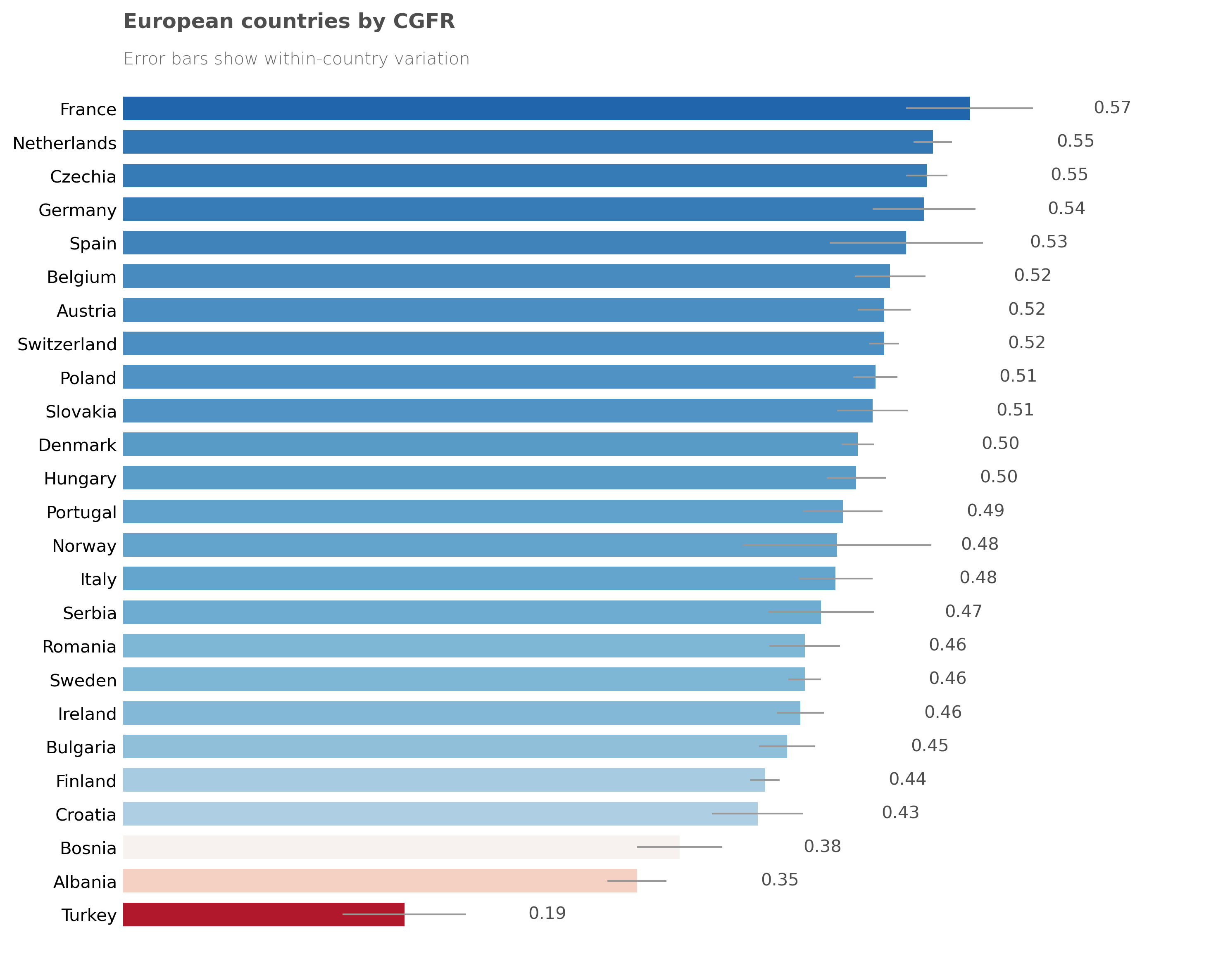

Turkey has the lowest CGFR among all European countries in the dataset.

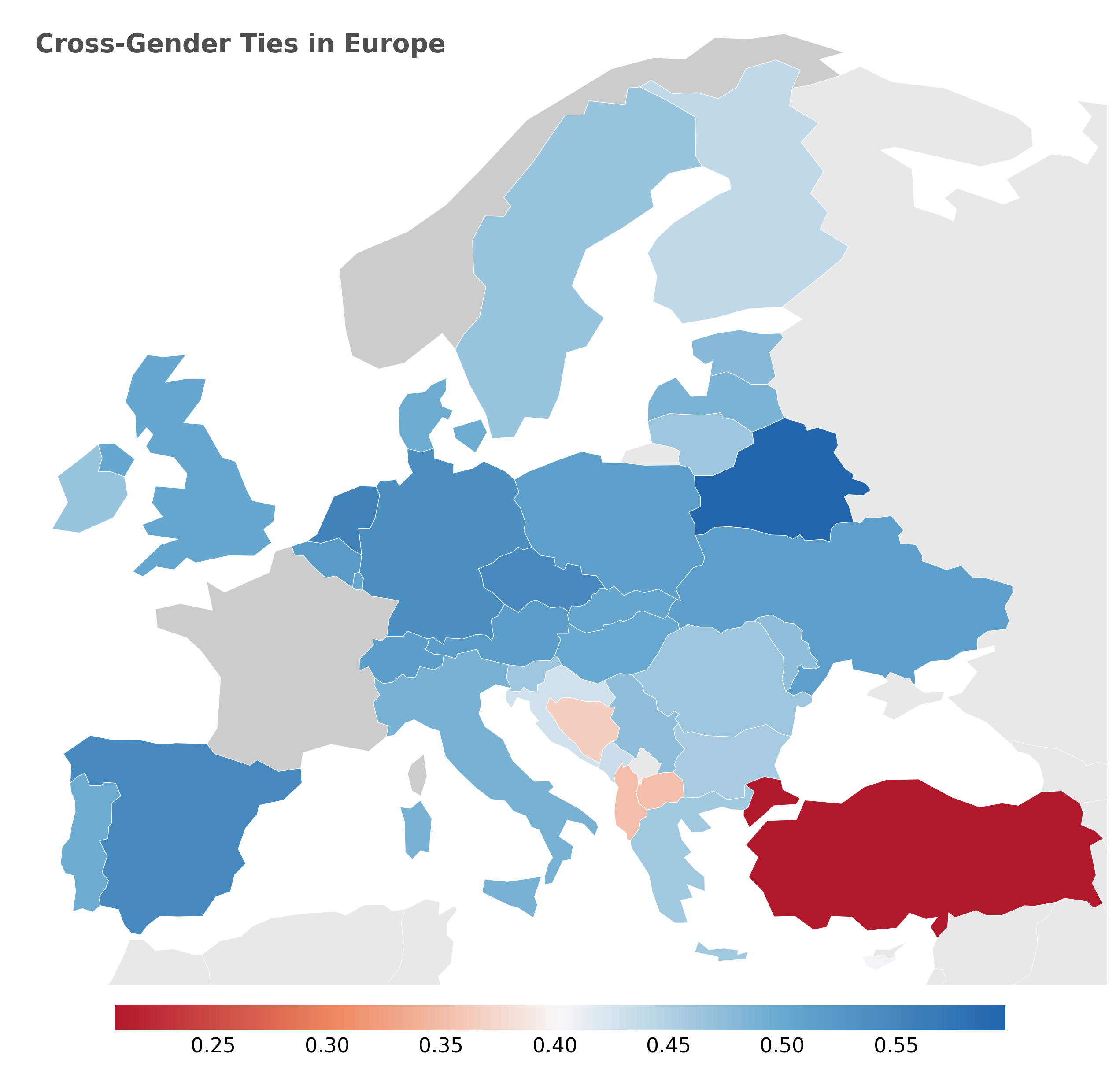

The European map makes Turkey’s position painfully clear. While Western and Northern Europe show generally higher values (blues and greens), Turkey stands out as the deepest red on the continent. Even neighboring Greece and Bulgaria — not known as bastions of gender equality — have substantially higher scores.

Global Patterns

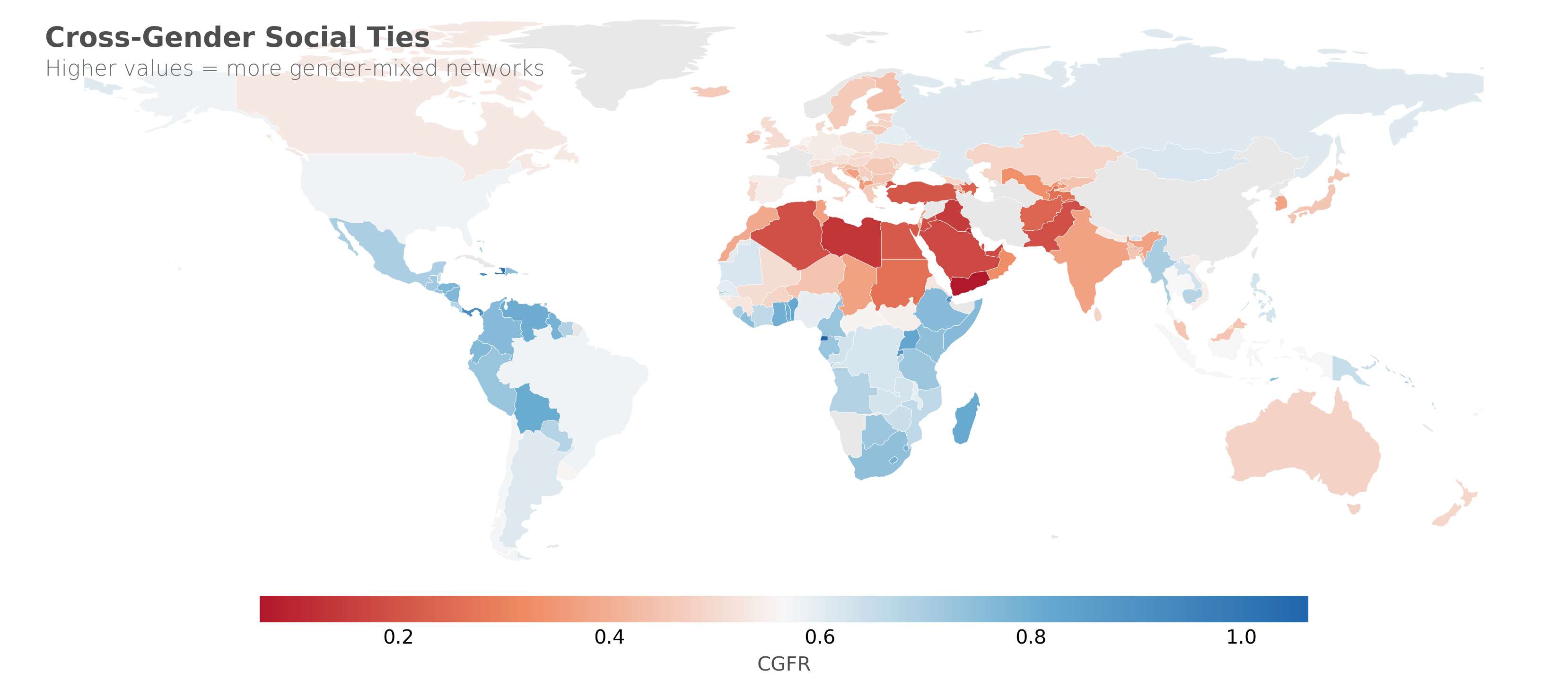

The world map reveals clear geographic patterns. The Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia show the lowest cross-gender social ties (red/orange). Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Caribbean show the highest values (green). Western Europe and North America fall in the middle.

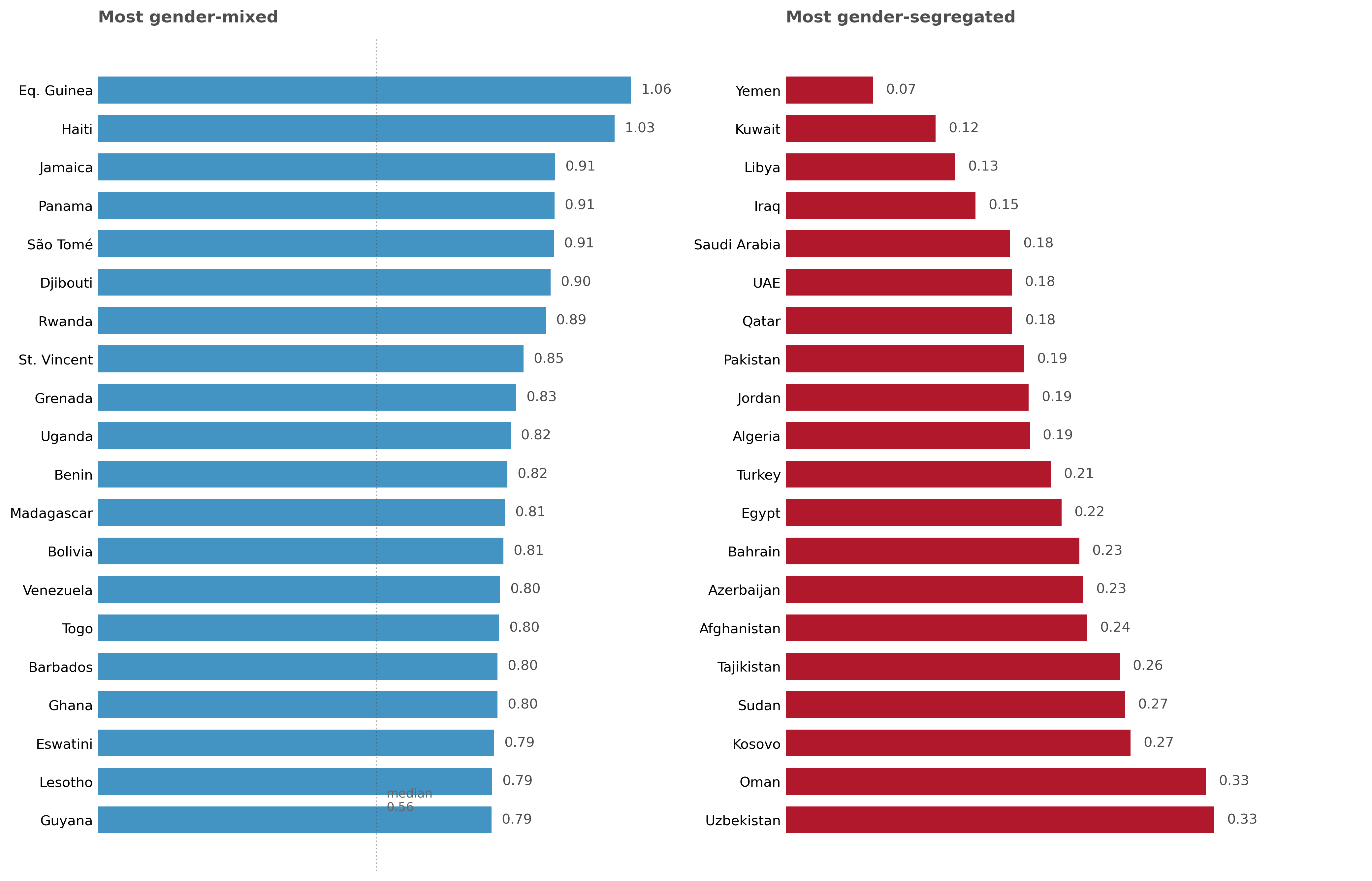

Jamaica and several Caribbean nations top the global rankings with CGFR values above 0.9, while Afghanistan has the lowest score (0.07). The distribution is roughly bimodal, with a cluster of countries around 0.2-0.3 and another around 0.5-0.7.

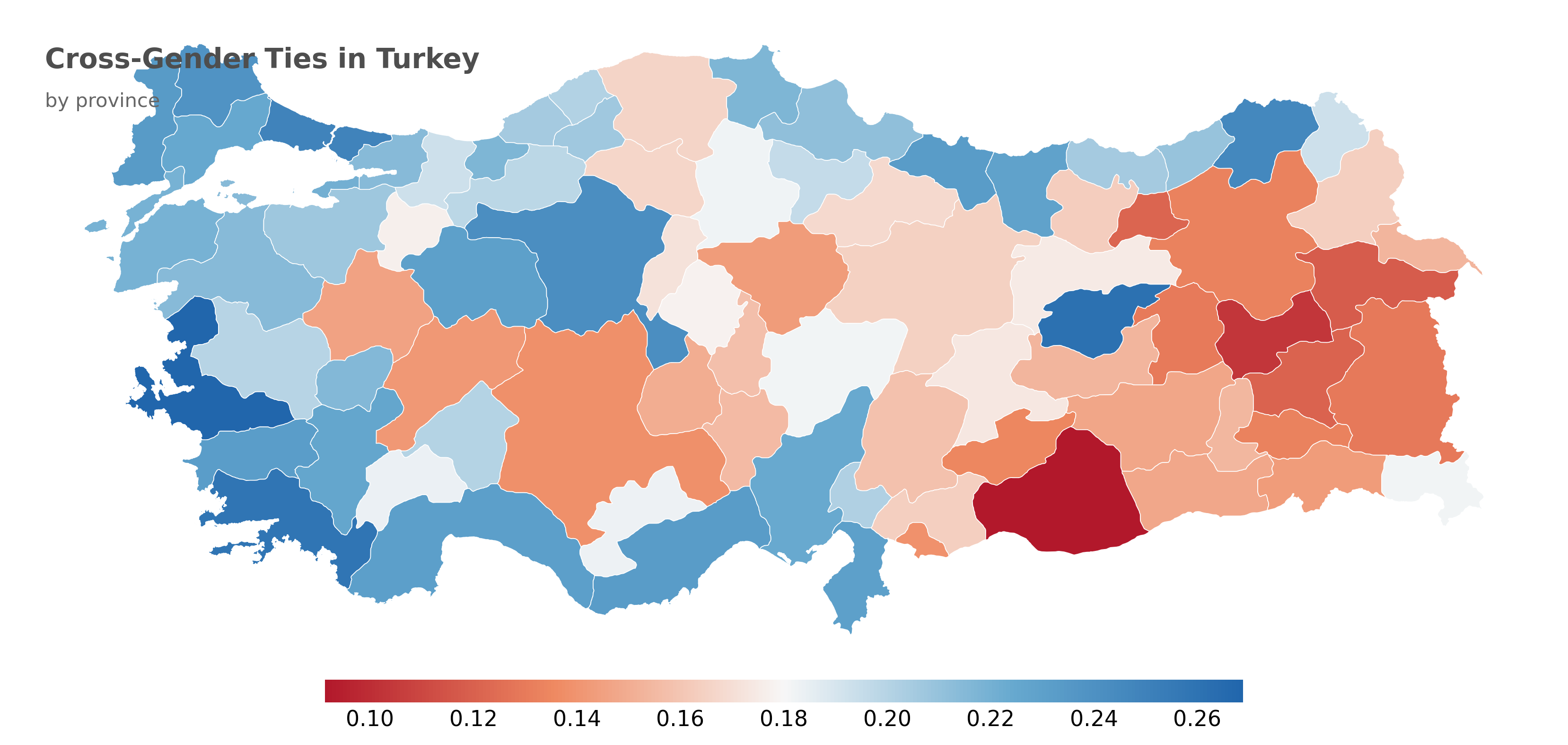

Regional Variation Within Turkey

The sub-national data for Turkey’s 81 provinces tells an interesting story. There’s a clear west-east gradient: western and coastal provinces (Istanbul, Izmir, Antalya, Muğla) have significantly higher cross-gender ties than southeastern provinces.

The highest-scoring provinces are along the Aegean and Mediterranean coasts, with values around 0.25-0.30. The lowest-scoring provinces are in the southeast, with values as low as 0.10. This pattern mirrors other socioeconomic indicators in Turkey, from education levels to GDP per capita.

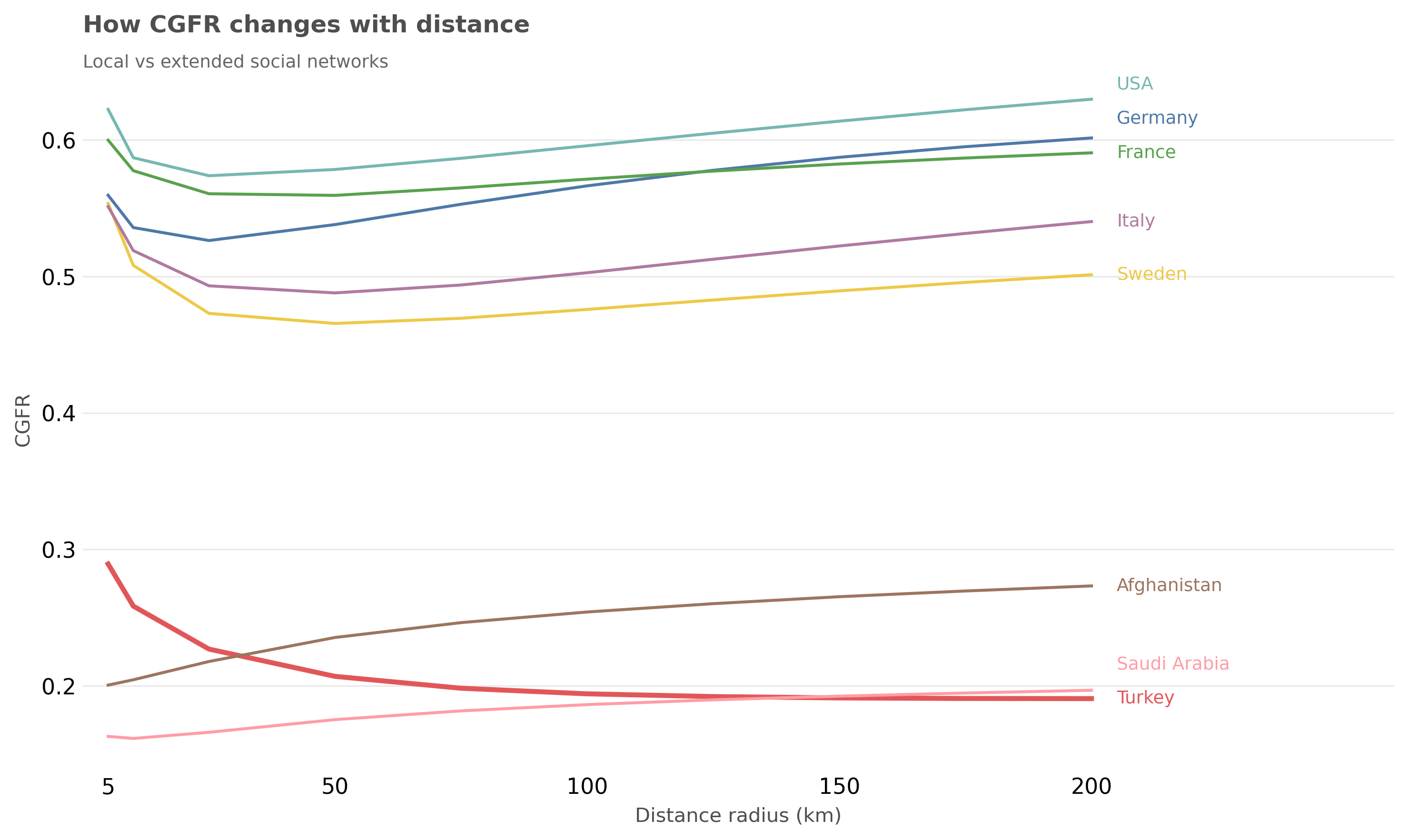

How Distance Changes the Picture

One of the more interesting aspects of the dataset is that it provides CGFR at multiple distance radii (5km to 200km). This allows us to see whether local social networks differ from extended ones.

The patterns vary dramatically by country. In Turkey, the CGFR is actually highest at very short distances (5km) and drops off as the radius increases. This suggests that immediate neighborhoods might have somewhat more gender-mixed interactions, but extended social networks become more segregated.

Contrast this with Western European countries like Sweden and Germany, where the CGFR stays relatively flat across all distances. In Saudi Arabia and Afghanistan, the ratio is low at all distances and barely changes with radius.

European Context

Looking at European regions (NUTS2 level), we see substantial within-country variation in most countries. The error bars show standard deviation across regions within each country. Turkey stands out not just for its low mean, but also for its relatively low within-country variation — the entire country is fairly uniformly segregated compared to, say, Italy or Spain where some regions differ substantially from the national average.

Culture vs Development: What Matters More?

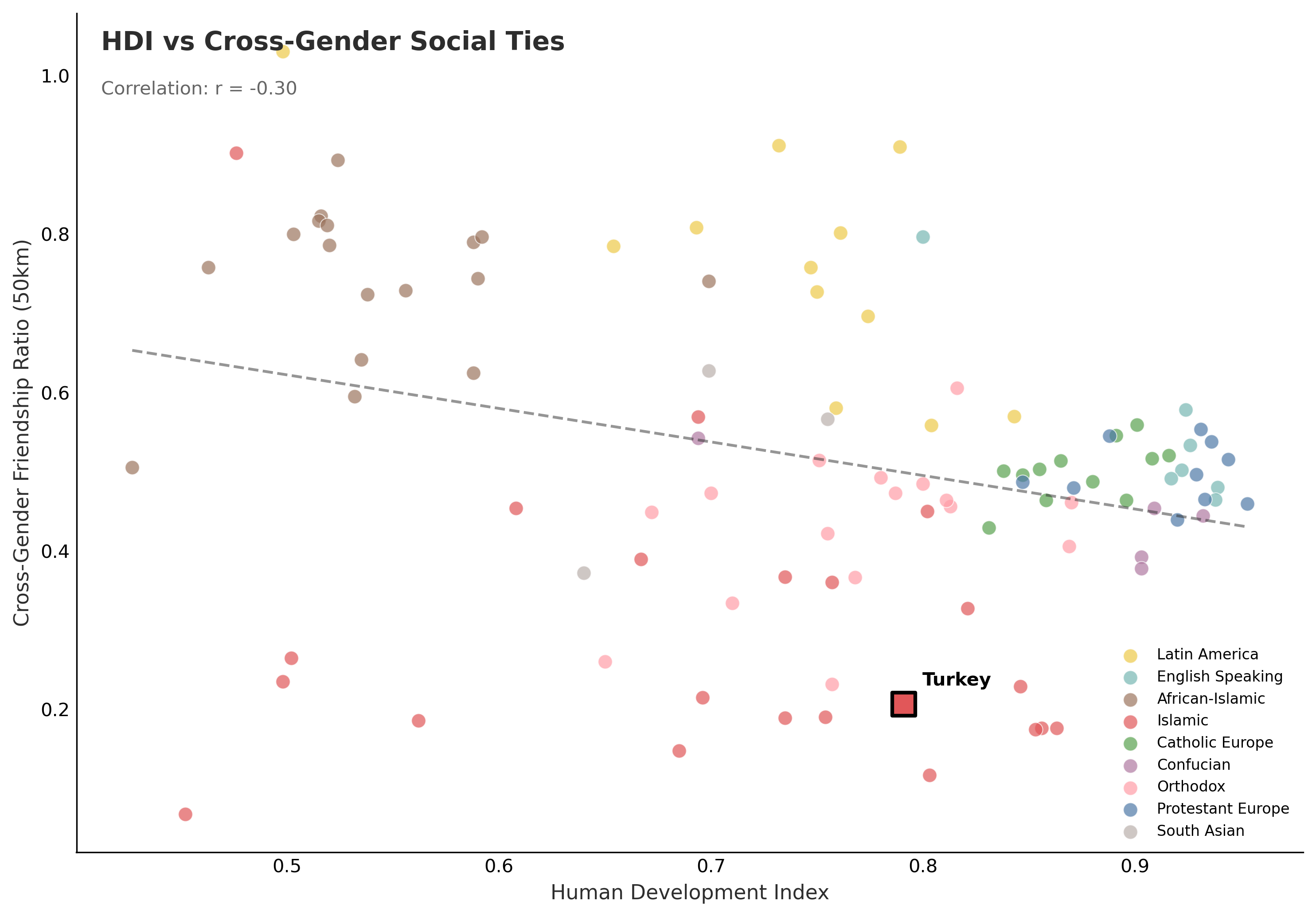

A natural question arises: is Turkey’s low CGFR due to its level of economic development, or is it something more cultural? To explore this, I merged the CGFR data with the Human Development Index and the Inglehart-Welzel Cultural Map classifications from the World Values Survey.

The first surprise: HDI and CGFR are weakly negatively correlated (r = -0.30). Countries with higher human development don’t systematically have more gender-mixed social networks. Latin American and Sub-Saharan African countries — many with moderate HDI — have some of the highest CGFR values globally. Meanwhile, developed countries like Japan and South Korea have relatively modest CGFR scores.

HDI alone explains only 9% of the variance in CGFR. Economic development is not destiny when it comes to gender mixing in social networks.

Culture tells a completely different story. When I group countries by the Inglehart-Welzel cultural clusters — derived from decades of World Values Survey data — the patterns become stark. Culture alone explains 67% of the variance in CGFR, compared to just 9% for HDI.

The rankings are striking:

- Latin America leads with the highest CGFR values (mean: 0.76)

- African-Islamic countries come second (mean: 0.77) — a heterogeneous group

- Protestant Europe, Catholic Europe, and English-Speaking countries cluster in the middle (0.50-0.55)

- Islamic countries have the lowest values (mean: 0.29), with massive variance

Turkey, marked by the red dashed line, falls at the very bottom of the Islamic cluster.

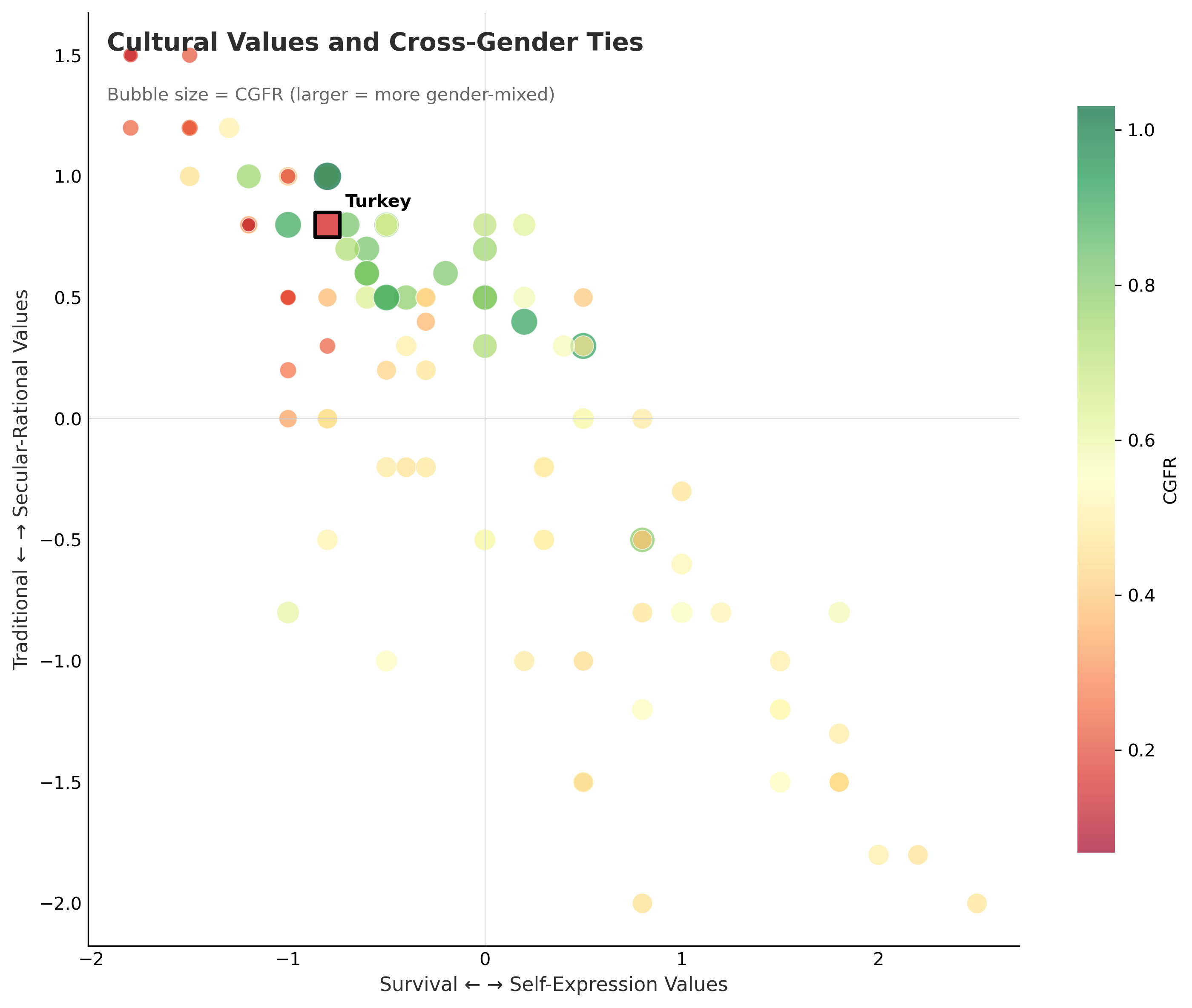

The Inglehart-Welzel cultural map positions societies along two dimensions: Traditional vs Secular-Rational values, and Survival vs Self-Expression values. In this space, we can see that countries in the lower-left quadrant (secular, self-expression oriented) tend to have higher CGFR — but the relationship is primarily driven by the self-expression axis (p < 0.0001) rather than the traditional-secular axis.

Turkey sits in the traditional/survival quadrant, which partly explains its low score. But even within that region, Turkey has one of the smallest bubbles — indicating its CGFR is lower than even its cultural neighbors would predict.

Turkey as an Outlier

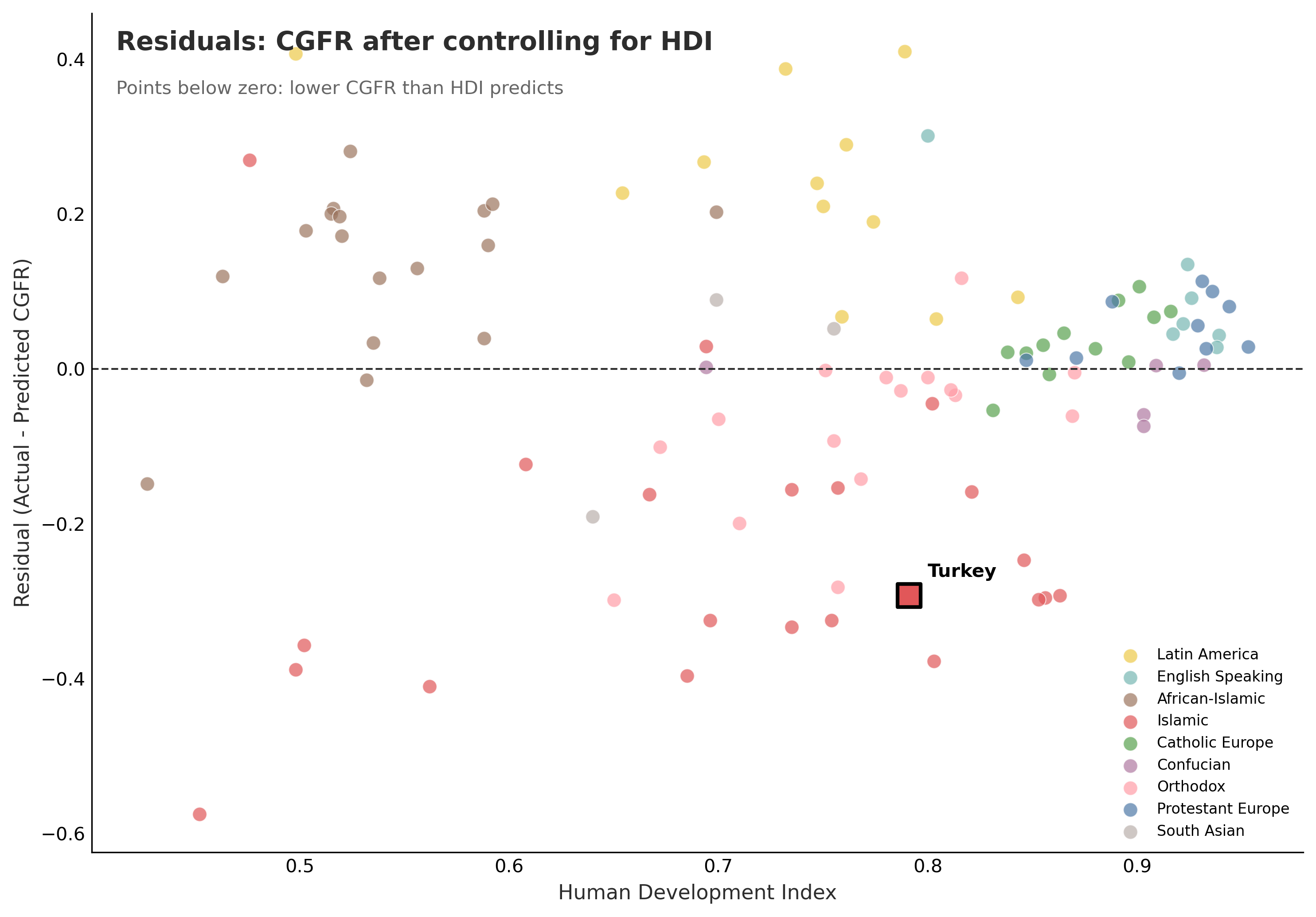

Perhaps the most revealing analysis is the residual plot. This shows how much each country’s CGFR deviates from what we’d predict based on HDI alone.

Turkey stands out as a dramatic negative outlier:

- HDI: 0.79 (medium-high development)

- Predicted CGFR (from HDI): 0.50

- Actual CGFR: 0.21

- Residual: -0.29

In plain terms: given Turkey’s level of development, we’d expect it to have roughly twice the cross-gender social mixing that it actually has. Something beyond economic development is driving Turkey’s exceptionally low score.

When we control for both HDI and culture, Turkey still underperforms. It’s not just that Turkey is in the Islamic cultural cluster — it’s at the extreme low end even within that group.

So Which Matters More?

The regression results are unambiguous: culture matters far more than development for predicting cross-gender social ties.

| Model | R² | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| HDI only | 9.1% | Weak predictor |

| Culture only | 67.0% | Strong predictor |

| HDI + Culture | 68.8% | HDI adds only 2 percentage points |

Even when we control for cultural region, HDI remains statistically significant — wealthier countries within each cultural cluster do have slightly more gender-mixed networks. But the effect is small. Moving from the lowest to highest HDI within a cultural group shifts CGFR by perhaps 0.1 points. Moving between cultural groups can shift it by 0.4 points or more.

For Turkey, this suggests that economic development alone won’t substantially change its gender-mixing patterns. The factors driving Turkey’s low CGFR appear to be more deeply cultural or structural in nature.

Why Is Turkey Such an Outlier?

The analysis above shows Turkey is an outlier, but doesn’t fully explain why. Let’s dig deeper by examining Turkey in two contexts: among European countries and among Muslim-majority countries.

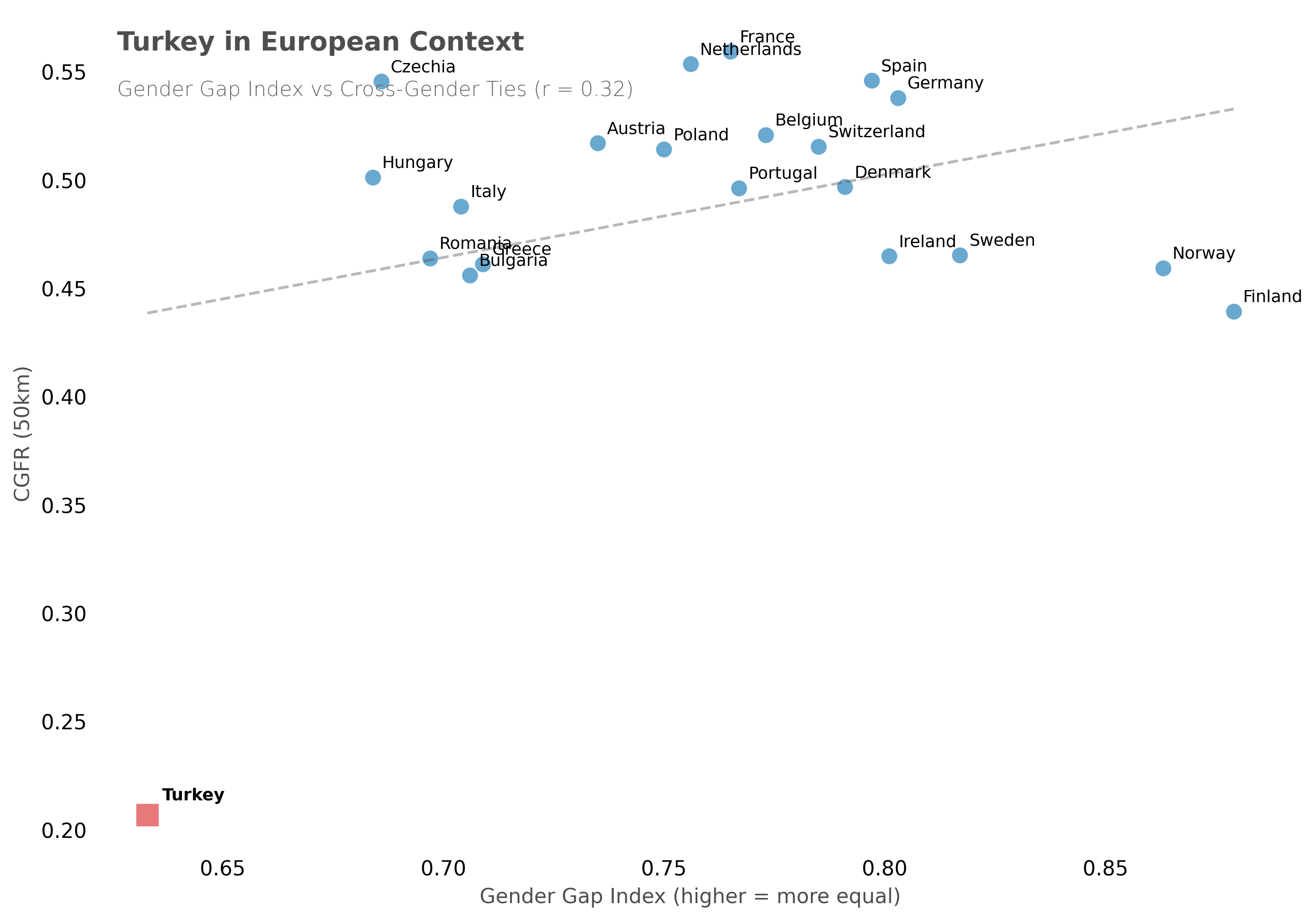

Turkey in European Context

Among European countries, there’s a modest positive correlation between the Gender Gap Index (GGI) and CGFR (r = 0.32). Countries with more formal gender equality also tend to have more gender-mixed social networks. Turkey, however, sits completely outside this relationship — far below all other European countries on both dimensions.

Turkey’s CGFR of 0.21 is 57% below the European mean of 0.49. The next-lowest European country (Albania at 0.35) still has nearly double Turkey’s score. Turkey isn’t just at the bottom of Europe; it’s in a different league entirely.

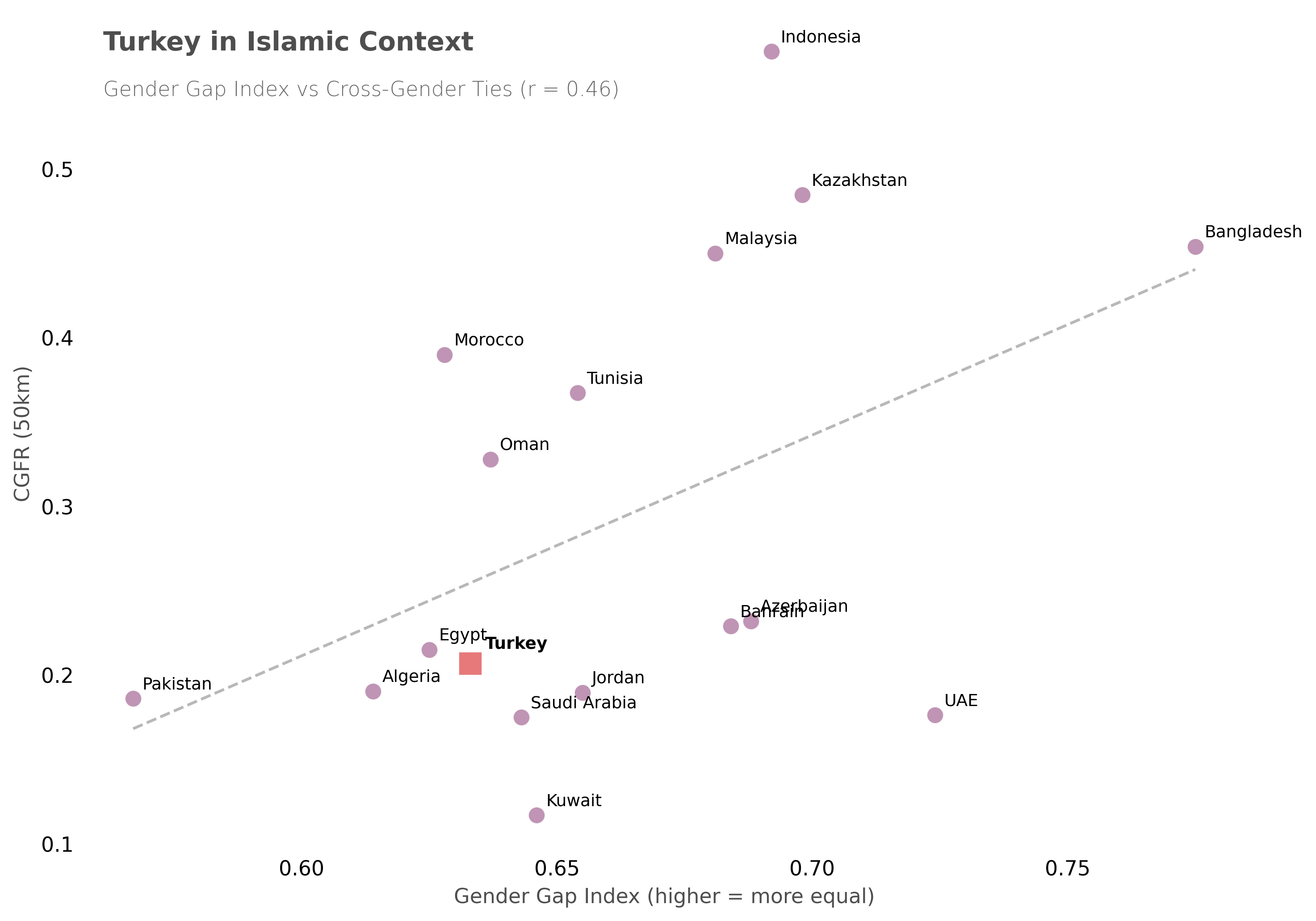

Turkey in Islamic Context

Perhaps more interesting is how Turkey compares to other Muslim-majority countries.

This comparison reveals a striking split within the Islamic world. Southeast Asian Muslim countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Kazakhstan) have remarkably high CGFR values — Indonesia at 0.57 is comparable to France. Meanwhile, Turkey clusters with the Arab Middle Eastern countries: Egypt, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Jordan.

Despite having similar GGI scores to Saudi Arabia (0.63 vs 0.64), Turkey’s CGFR is lower (0.21 vs 0.18). And Turkey has much lower CGFR than Muslim-majority countries with similar or lower development levels:

| Country | GGI | CGFR | Difference from Turkey |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | 0.69 | 0.57 | +175% |

| Bangladesh | 0.78 | 0.45 | +117% |

| Malaysia | 0.68 | 0.45 | +117% |

| Morocco | 0.63 | 0.39 | +86% |

| Turkey | 0.63 | 0.21 | — |

The Indonesia comparison is particularly stark. Indonesia has:

- Similar population size

- Lower urbanization (57% vs 77%)

- Lower HDI (0.71 vs 0.79)

- Yet CGFR is nearly 3x higher than Turkey

What Explains This?

Several hypotheses emerge:

Regional cultural influence: Turkey may be more influenced by Middle Eastern social norms than Southeast Asian Muslim countries, which have different pre-Islamic cultural traditions.

Urbanization patterns: While Turkey is more urbanized overall, the type of urbanization matters. Turkey’s urban growth was largely rural-to-urban migration from conservative eastern provinces, potentially bringing traditional gender norms to cities.

Political trajectory: The past two decades have seen significant social changes in Turkey that may have reinforced traditional gender segregation.

Measurement artifact: Facebook usage patterns might differ — Turkish users may preferentially friend same-gender contacts for cultural reasons even if they interact with opposite-gender people in daily life.

The data can’t definitively answer which of these explanations is correct, but it’s clear that Turkey’s low CGFR is not simply a function of being a Muslim-majority country. Something specific to Turkey’s social structure produces gender segregation at levels unusual even for the Middle East.

Some Caveats

A few important notes about interpreting this data:

It’s based on Facebook friendships, which may not perfectly reflect real-world social ties. Facebook adoption rates, user demographics, and friending behaviors vary across cultures.

CGFR measures quantity, not quality. Having many cross-gender Facebook friends doesn’t necessarily mean deep, meaningful relationships.

The data is observational. It can’t tell us why some places have more gender-segregated networks than others — whether it’s due to cultural norms, religious practices, economic factors, or something else entirely.

Privacy restrictions mean no individual-level data. The ratios are computed at regional levels, so we can’t see variation across different demographic groups within a region.

Despite these limitations, the patterns are clear and largely consistent with what we know from other research on gender segregation and social capital.

What This Means

The cross-gender ties metric is, in a sense, a proxy for something broader: how much do men and women in a society interact as equals in everyday social life? Low values suggest parallel social worlds — men spending time mostly with men, women with women. High values suggest more integrated social networks.

The implications touch on everything from economic participation (it’s hard to advance in a field if you can’t network with colleagues of the opposite gender) to political representation to simply the texture of everyday life. Countries with more gender-mixed social networks tend to score higher on various measures of gender equality, though the causal direction is unclear.

For Turkey specifically, the regional variation offers a natural experiment of sorts. Comparing outcomes between high-CGFR western provinces and low-CGFR eastern provinces — while controlling for other factors — could shed light on how social network structure relates to economic and social outcomes.

Data source: Cross Gender Ties dataset from Meta’s Data for Good team.

Paper: Johnston, Drew et al. “Cross-Gender Social Ties Around the World” (PDF)